His studies were instrumental in this transition. Establishing a firm historical foundation, he embarked on more inventive exercises. This was a beginning rather than an end for Piranesi. ‘Piranesi’s genius lay in print, specifically in the exploration of the realms outside extant architecture the unbuilt, the demolished and the derelict’ In an age of digital reconstructions of long-lost environments, set to deepen with advances in AR and VR technology, our debt to Piranesi will only increase. Indeed, it was recognised as such immediately, with the Society of Antiquaries in London electing Piranesi an Honorary Fellow in 1757. In an age when archaeology was still in relative infancy, the study was invaluable and remains so, given how many of the monuments have been physically lost to us in the intervening years. Beginning initially as a documentation of funereal architecture, the central project of his entire career, the Antichità Romane, became an immense recording of Roman antiquity, numbering 250 plates and four volumes in total. Travelling as part of a Venetian papal delegation, he became fascinated with the remains of Ancient Rome, and argued for its importance against an intellectual consensus that had deemed it inferior to Ancient Greece. Image courtesy of Dietmar Katz / Kunstbibliothek der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlinīefore creating his fictions, Piranesi had first mastered the study of surviving architecture. Sketch of an altar for the Church of Santa Maria del Priorato on Rome’s Aventine Hill. Enthralled by antiquity, he chose the medium of etching and printmaking, which seemed to embody within it the passage of time, giving even his invented works the sense of having a past. While he is buried at the Church of St Mary on the Aventine, a minor treasure he worked to restore between 17, his genius lay in print, specifically in the exploration of the realms outside extant architecture the unbuilt, the demolished and the derelict.Ī Venetian by birth and outlook, he belonged to the capriccio tradition of imaginary, or composite, cityscapes.

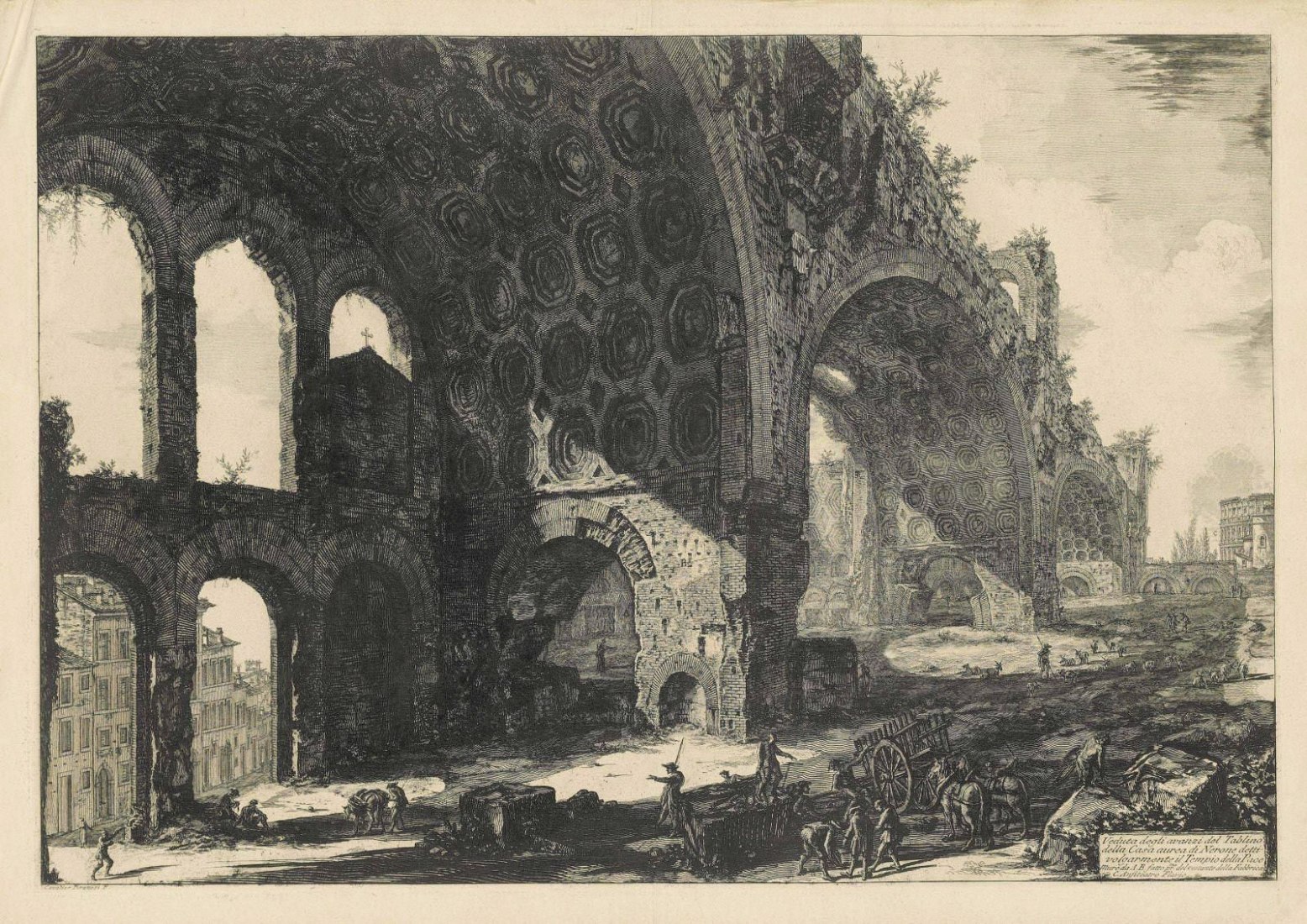

While proudly declaring himself an architect, Piranesi built very little. The latter was an artist and an architect a Venetian and a Roman the last of the Ancients and the first of the moderns a visionary who studiously documented imperial ruins while predicting the ‘dark Satanic mills’, in Blake’s words, of the coming Industrial Revolution a prophet who spent his days recreating the past a designer of heaven and hell. Often depicted with two faces gazing in opposite directions, this was a god who reflected Piranesi’s nature. Its colossal arches hinted at the nature of the Roman god to whom it was dedicated – Janus, the god of gateways, journeys and change. The range of his artistic productions-from objective architectural plans to elaborate architectural fantasies, from urban scenes of eighteenth-century Rome to imaginary scenes of subterranean torture-demonstrate visually many of the thematic tensions that animate literary works of the following decades.In 1748, Giovanni Battista Piranesi depicted the Temple of Janus overgrown and in a state of disrepair. Piranesi’s works straddle the boundary between neoclassicism’s emphasis on order and the classical ideal and Romanticism’s emphasis on the imagination and the individual.

In this seminar, Piranesi’s visual meditations on the lost glories, shadowy corners, and persistent beauty of ancient Roman architecture served to introduce students to the literary and cultural period of Romanticism.

#PIRANESI ARCHITECTURE PROFESSIONAL#

In Spring 2017 I taught an honors college seminar that met in Rare Books and Special Collections called “Piranesi and Romanticism: Architecture and the Literary Imagination.”īorn in Venice, Piranesi made his professional and cultural home in Rome, where his works were sold individually and bound in publications including Antichità romane (1756), Vedute di Roma (1748), and Carceri d’invenzione (1750). Piranesi’s works reveal significant transitions in archaeology, aesthetics, architecture, engraving, and print, and they inspired many of the great names of nineteenth-century literature. He is known for his meticulous and fanciful engravings of Roman architecture, ancient and modern, as well as his “imaginary prisons.” In his engravings, lush vines hang over classical ruins, eighteenth-century scholars cast light in the shadows of long-hidden family crypts, and faceless prisoners climb endless staircases past skulls and bones. The University of South Carolina is one of six institutions worldwide to own a complete twenty-nine volume set of the works of the eighteenth-century architectural illustrator Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)